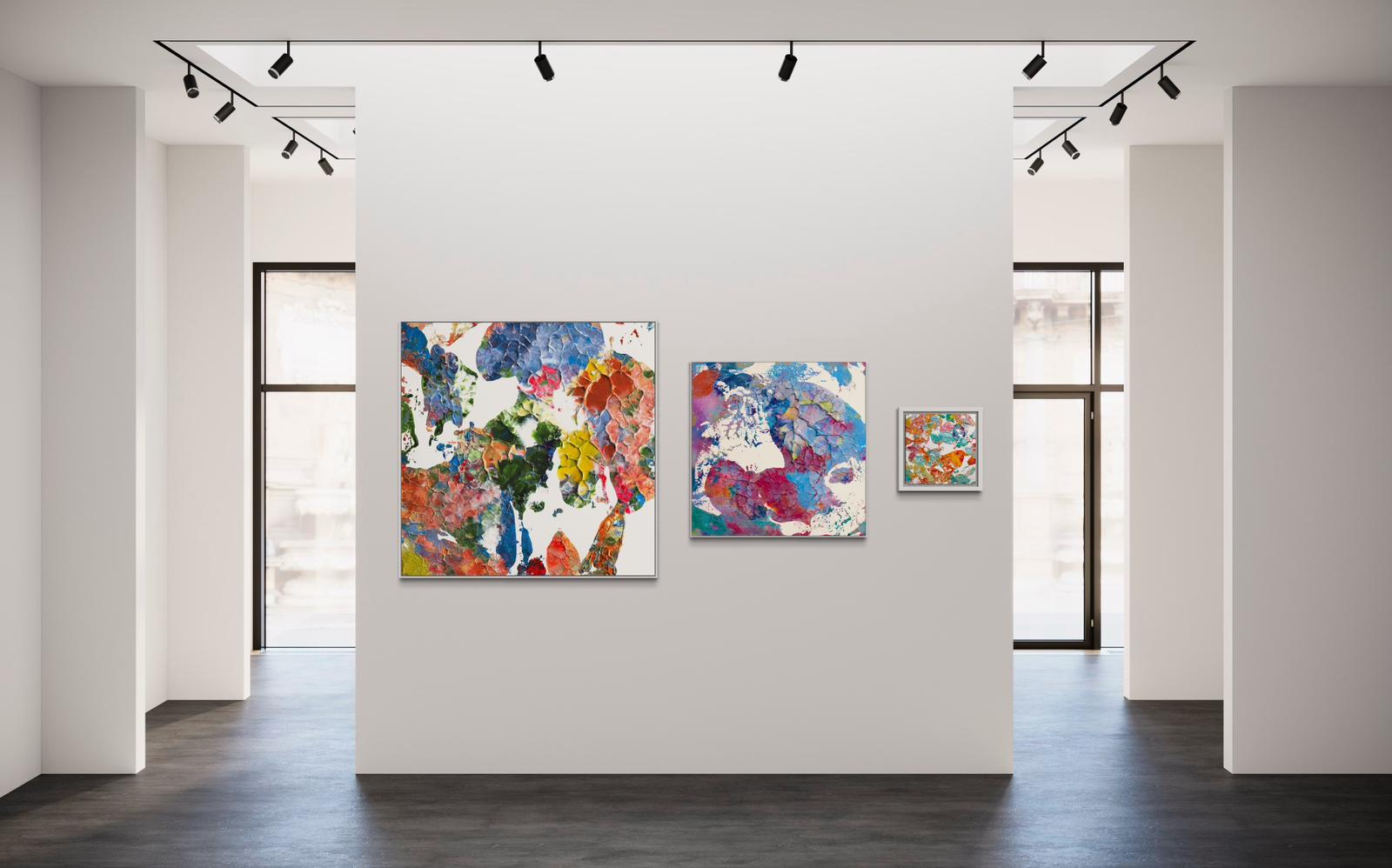

LEAVES IN LOVE | Limited Edition Canvases

ABOUT THE SERIES

Leaves in Love – A Journey Through Colour, Texture, and Transformation

Many cultures embrace the notion of impermanence, the idea that a soul traverses realms carrying energy, both positive and negative. These beliefs highlight the importance of living with awareness, cultivating a compassionate world, and ultimately departing this existence in a state of love. To leave in love is to progress with grace, carrying forward a luminous energy into the unknown, to the next state, whatever that may be. And therein lies the possibility of evolution, of redemption.

One bright morning when I was around twelve years old, I encountered a fragile bird lying on a bed of leaves. In my youthful recklessness, I had unknowingly set in motion an irreversible moment. Seeing the bird’s stillness, I was struck by the delicate, transient nature of life. In that moment, I recognised the power of intention, the unseen imprints we leave on the world, and the silent lessons nature offers when we pause to listen. Ever since, through the ebb and flow of life’s joys and struggles, that morning has remained a guide, a lesson in compassion, presence, and the interconnectedness of all living things.

A Meditation on Impermanence

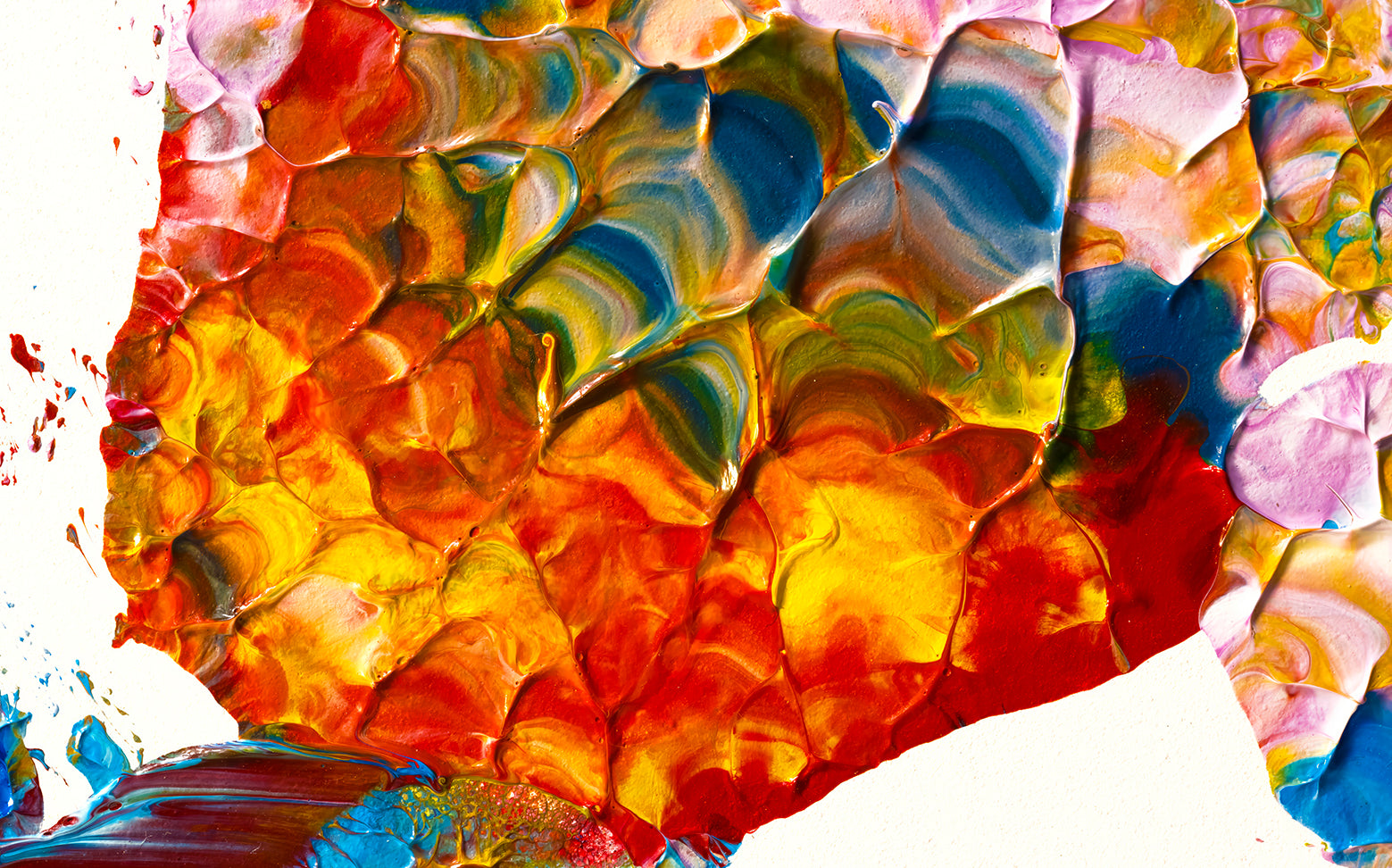

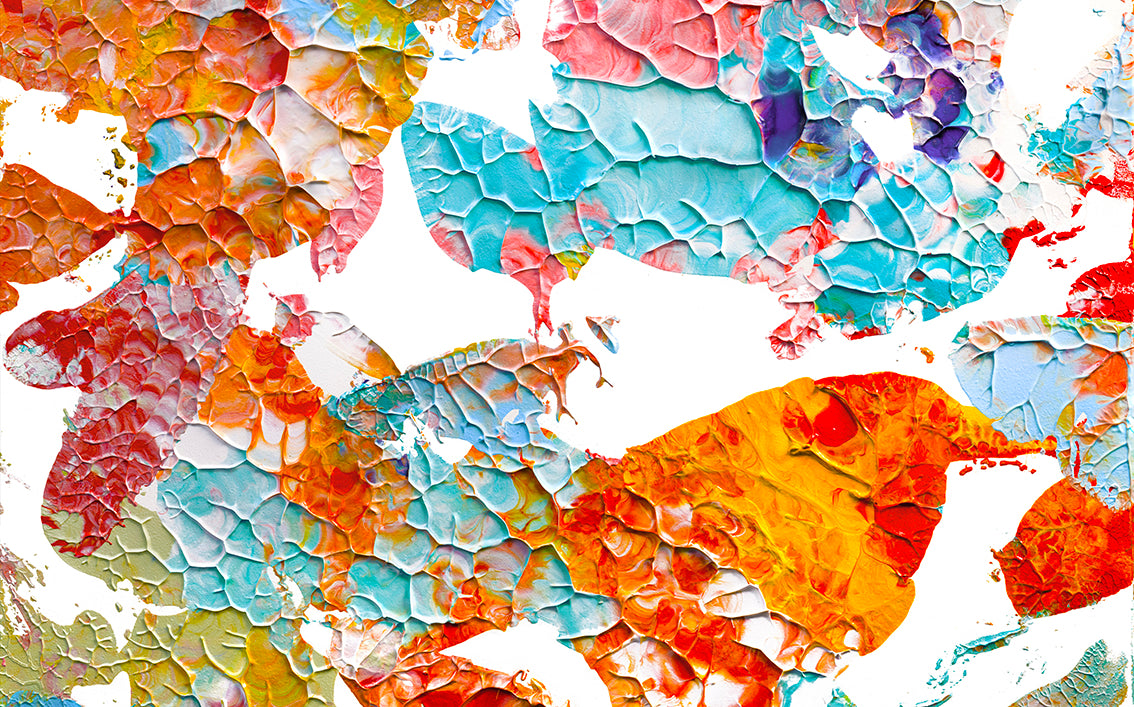

Like the shifting seasons, Leaves in Love embodies change. The works emerge from layers of experience, mirroring the idea that no life, no moment, and no creation remains the same. Each painting begins as a physical oil painting and is then reimagined through photography, revealing intricate textures and hidden details that blossom into new dimensions. Each transformation, canvas to print, small to large, oil to pigment, speaks to the fluid nature of existence.

Each change in medium or scale alters the image, the meaning, and evokes new apprehensions in unexpected and sometimes revelatory ways. All is in a state of flux, and the boundaries between states are permeable.

Inspired By…

Visits to Dhanakosa Retreat in Balquhidder, Scotland, and Butchart Gardens in Brentwood Bay, Canada. Two landscapes, thousands of miles apart, yet both resonating with the same stillness, the same quiet whisper of leaves in the wind. Their rich palettes informed the colours and textures in this collection, inviting collective contemplation through a play of scale, detail, and abstraction.

The works are the passage of a soul that has never been ‘mine’. It is not a possession but rather a fractal akin to a bird or a leaf on a tree I have been privileged to assume for a time.

A Canvas in Flux

In The Conference of the Birds, the Persian poet Farid al-Din Attar tells of a quest for meaning that ends with self-realisation. Like the wise hoopoe gazing into the mirror, we, too, seek answers in the external world only to find them reflected within.

Each shift in medium or scale, painting to photograph to print, alters the image, deepening its meaning and revealing new perspectives. Every piece in Leaves in Love exists in a state of flux, and just as leaves drift and turn with the wind, these artworks invite us to embrace change and find beauty in the moment.

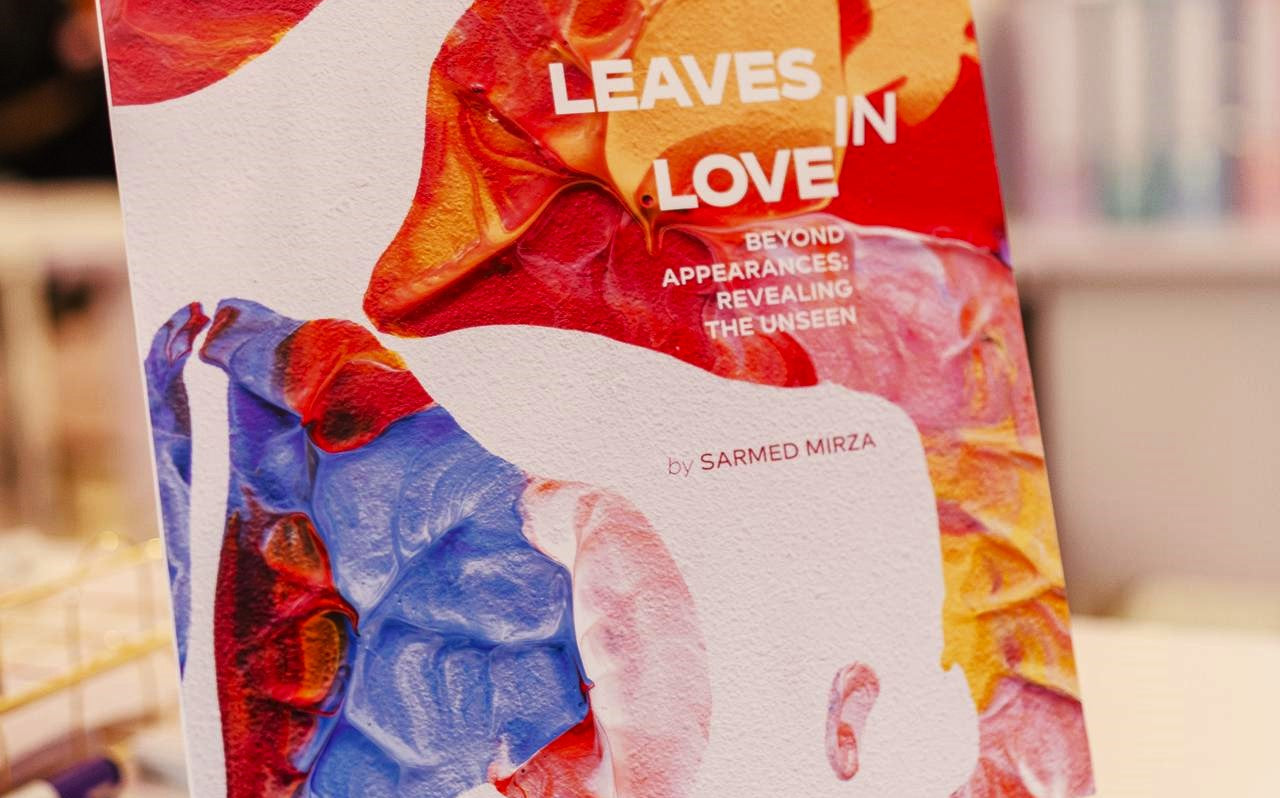

The pun in the title, of course, is deliberate; it suggests dying, departing on a journey, as well as the leaves of a book or tree. Yet, rather than being frozen in time, Leaves in Love intends to insinuate life, change, movement, and above all, hope, nudging us to notice what is right within us, right in front of our eyes.

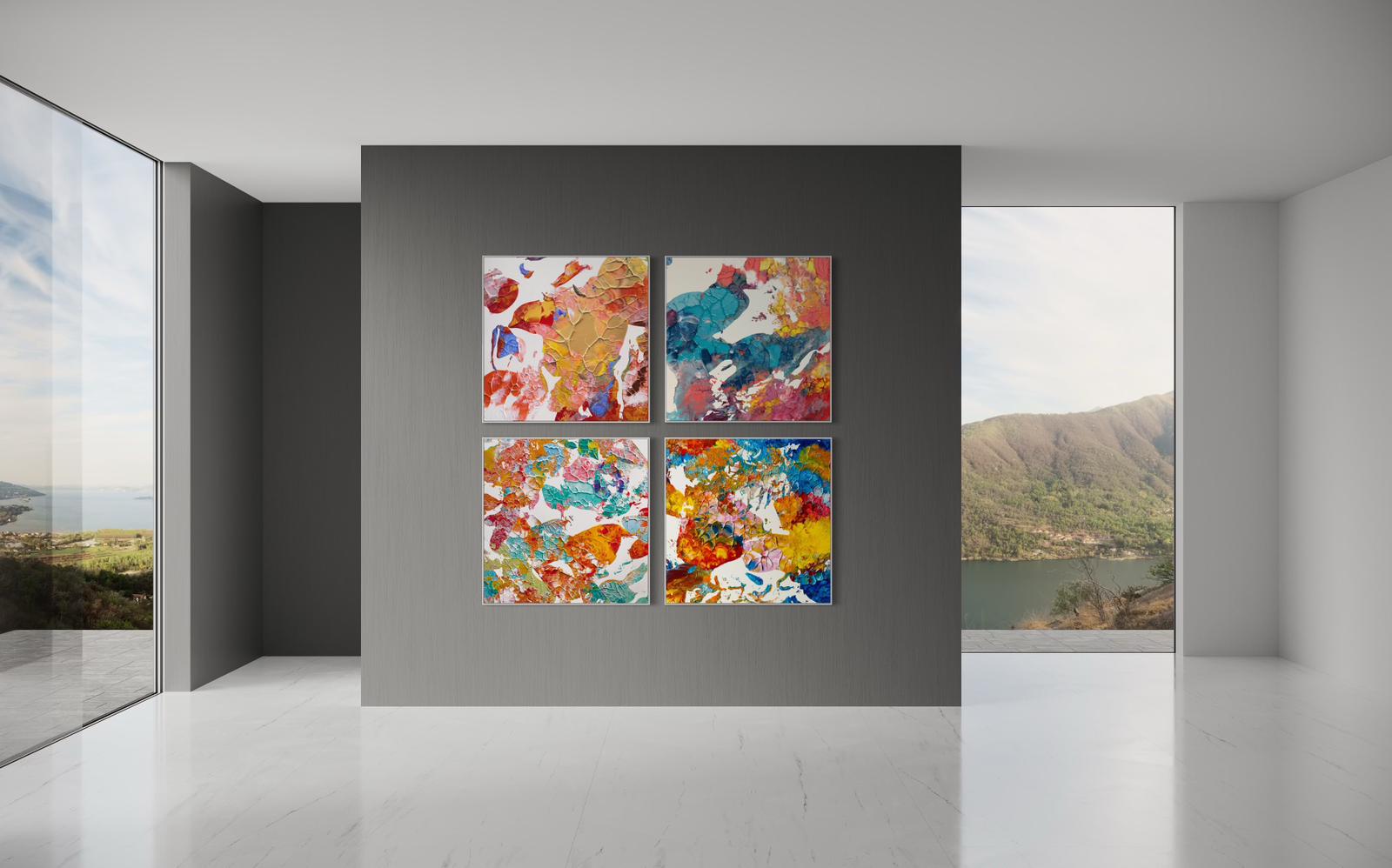

A Collector’s Offering – The Original Set

To honour the full depth of the Leaves in Love journey, collectors can acquire a special Original Set, which includes:

- A hand-painted original from the series.

- A large-format print of the chosen original.

- Four “Moments” prints (40x40cm each), capturing the essence of the collection.

- An art book detailing the creative process, inspiration, and philosophy behind the works.

Each piece in this collection is a fragment of a larger journey, one that you are invited to continue.

Revealing the Unseen

Through high-resolution photography, every handcrafted mark, colour, and shape from the oil paintings is captured and reimagined. These pigment prints are not mere reproductions but artworks in their own right, allowing new forms of engagement with the original textures and depths. No AI or artificial digital manipulation has been used in the creation of these works, only the pure translation of paint, light, and time.

Limited Edition Canvases

Each piece in Leaves in Love is available in three exclusive sizes:

- 145x145cm (Edition of 1) – Includes a hand-stitched folio.

- 120x120cm (Edition of 2)

- 100x100cm (Edition of 3)

Each print is hand-signed and numbered, ensuring its place as part of a rare and meaningful collection.

A Journey Together

Leaves in Love is an invitation to slow down, to observe, to feel. It is a visual meditation on impermanence, a call to appreciate the beauty that surrounds us, and a reminder that art, like life, is ever-evolving. It is about leaving this world in love, embracing the transitions, and departing towards the next state, whatever that may be, imbued with grace, compassion, and the imprint of love.

I hope you will enjoy Leaves in Love, as we journey together.